Sometime around 2500-3000 years ago, a deer hunter sat down by an earth oven with a hafted flint drill and began to bore into the bone of the front left hock of a recent kill.

The likely objective was removing its marrow and grease- one of the few sources of vital nutritious fat to be found on the typically lean prey animals in the area. The hunter was in a heavily occupied camp along a waterway now called Salado Creek in “The Land of Good Water” in north Williamson County, not far from the Gault Site. The hunter had likely traveled to and from the camp year after year as did many generations of ancestors. As fate would have it the deer hunter never finished the task, leaving behind a unique glimpse into a long-forgotten game process, but two or three millennia later Michael Boutwell of Leander, the next one to come along and uncover the scene, offers some insight.

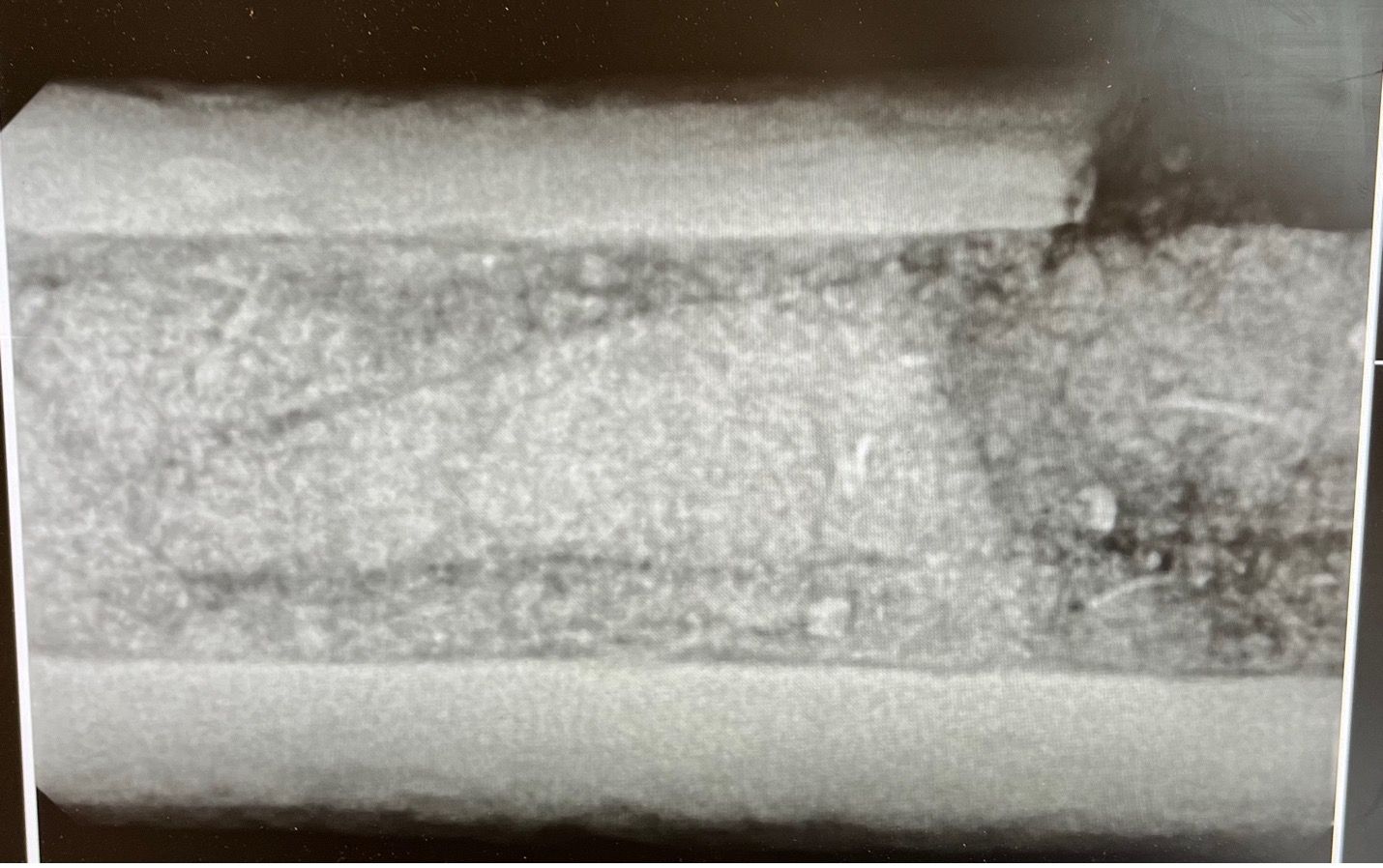

Boutwell, who appeared in Texas Cache Volume 24, #1 in 2020 holding a large metate from the Hogeye site in Elgin, is an ardent artifact hunter with an outstanding personal collection. He showcases many of his finds in-situ on social media under the handle @Manolithics. One of his intriguing finds is this Pedernales-style drill with the distal point embedded in the shaft of a whitetail deer (Odocoileus virginianus texanus) humerus. The visible part of the drill has a deep basal-notched split stem with parallel edges with the point partially exposed and stuck into the bone shaft.

“This bone fell out of the wall with the drill going up inside of the stem,” Boutwell expounds on the discovery, saying that the artifact was “found right outside of the main midden. The center point of this particular camp runs about 6 feet in depth at the deepest point.”

He goes on to report that it was dug from a depth of about 18 inches with the bedrock being about 30 inches deep, about 20 feet due west from the center of the midden.

Other projectile point types associated with this artifact are mostly Marshall along with Pedernales, Lange, and Travis, says Boutwell. “There have been two broke Early Triangles and one broke Andice, so there is evidence of older occupants. However, all of the early archaic fragments were found above the mid to late archaic layers so my guess is that those were picked up and brought in by the mid/late archaic cultures and reused.”

Other game likely encountered along the waterway were catfish, eel, alligator, and bear. Watercress would have been an abundant garnish. For this particular cut of venison, the hunter had presumably butchered the shoulder chuck and shank and had progressed to smaller-scale localized processing. Whatever the drill was hafted to has been lost to the ravishes of time but the stone and bone remained intact within the ashen matrix of the burned-rock midden.

Texas Beyond History explains on their website that, like bone stock we make today, after marrow was extracted, prehistoric Indians “then boiled the bones to get a rich and nutritious greasy broth. This process was called ‘bone greasing’.” Additionally, “The fat was later mixed with dried meat and other foods… that could be preserved and carried on hunting trips and from camp to camp.” (Reference 1)

Employing the help of a friend in the dental industry, Boutwell was able to obtain this radiographic image revealing the full drill tip extending into the interior cavity of the bone shaft with the matrix soil within the column holding it in place.

While hunter-gatherers are sometimes presumed to have been living a day-to-day, hand to mouth subsistence through immediate consumption of seasonal and regional foods encountered during interminable travel, there is solid evidence dating far into paleo-prehistory that marrow --specifically venison leg-- was effectively preserved and stored for future consumption. In 2019 Researchers from the American Friends of Tel Aviv University presented extensive evidence of fallow deer leg marrow being stored and preserved in Qesem Cave in present-day Israel during the Asiatic late lower paleolithic period. Their research showed that while other edible venison cuts were immediately skinned and butchered after killing, legs were stowed away with the soft tissue kept intact, rendering the bone marrow effectively “canned” for future use. Subsequent experiments by the researchers led them to conclude that storing leg marrow in this fashion resulted in a shelf life of about nine weeks. (Reference 2)

With the paleolithic period in the Middle East extending hundreds of thousands of years further into the past than the paleolithic timeline in North America, it is reasonable to assume that if this knowledge of marrow preservation was already in place that long ago, it could have been deeply ingrained in the hunting and gathering practices of the transcontinental travelers who branched out from that part of the world and eventually made it to modern-day Central Texas. Furthermore, limestone caves, sinkholes, and rockshelters located within close proximity of Salado Creek, Texas could have potentially offered similar environmental conditions to the caves near Tel Aviv.

At first glance, drilling into the shaft to get to the marrow seems more tedious than removing it from the lengthwise cavity that a spirally-fractured bone provides. Perhaps we’re looking at an attempt to bore the rim of the bone shaft to prepare it for hafting, or an attempt at making a tool, pipestem, or other utilitarian implement? Boutwell doesn’t think so; he believes the goal was indeed marrow extraction. If so, it gives a stark visual example of the importance of venison marrow to the archaic diet and the meticulous technology that people from that period might have employed to procure it.

Prehistoric bones thought to have been broken by humans with the intention of extracting marrow are often purposefully twisted and cracked in long spiral fractures along the shaft, resulting in a lengthwise trough-shaped cavity allowing easier access to scoop the protein-rich marrow. Boutwell’s bone appears to have been broken by snapping, resulting in a deep narrow circular cavity. The top and middle photos offer a comparison of Boutwell’s piece to a modern white-tailed deer humerus snapped in half, resulting in a similar fracture pattern to the artifact. Distal ends of both examples remain intact. One consideration that should be taken into this context, however, is that bone might fracture differently depending on how long the tissue has been dead. A wet or “green” bone broken very soon after the kill might separate in markedly disparate patterns from a preserved or aged bone broken in the same manner. The modern bone was snapped several months after the death of the deer. Bottom photo: two examples of deer bones with spiral-fractures from Waco Lake. (Photo courtesy of texasbeyondhistory.net.)

Many thanks to Michael Boutwell for providing a close look at this unique piece of prehistory and offering his thoughts and information about it. Upon mention of the “Excalibur” notion of removing the drill, Michael says “It’s been left inside the bone to this day. I do not plan to take it out.” Texas Cache concurs.

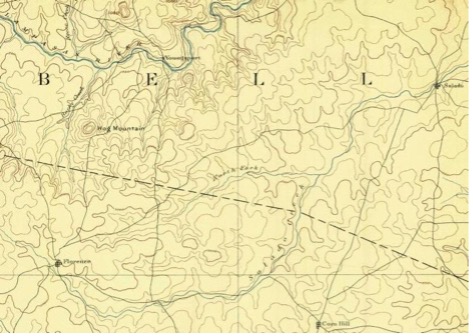

Which Salado Creek?

There are no less than Five Salado Creeks in Texas: in Bexar, Maverick, Webb, Zapata, and Williamson/Bell Counties. Boutwell found his drill and bone on the Salado Creek that originates in Williamson County and runs into Bell County through its namesake town. Locals and old-timers often refer to the waterway as Salao, Salow, or Saliow; this common bastardization of the name applies to the creek only and not the town. (Reference 3).

Historian Charlene Carson states on her Central Texas Stories website that "Salado Creek rises in two forks around Florence in northwestern Williamson County, unites in southern Bell County, and flows 35 miles northeastward to join the Lampasas River in the area known as Three Forks. At that point, the Salado, the Lampasas, and the Leon Rivers all unite to form Little River; the Little River flows into the Brazos River which flows into the Gulf of Mexico."

In 1836, Little Creek Fort was established near Three Forks. It was later renamed Fort Smith, again renamed Fort Griffin, and ultimately abandoned in 1841.

Spanish explorers referred to Salado Creek as the Salt Fork of the Lampasas River," continues Carson. "It acquired the name Salado, Spanish for salt, because of the salty taste of the water from the sulphur springs that flowed along its course." (Reference 4).

For further reading, Carson co-authored a book with Mary Harrison Hodge titled Images of America SALADO by Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

(C) 2023 Texas Cache Magazine, All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced without attribution to the following citation:

Murray, Ryan. "A Stone In A Bone", Texas Cache Magazine, Vol. 26 #3, Fall 2023, pp 12-15. https://texascachemagazine.com/a-stone-in-a-bone

No part of this article was generated by Artificial Intelligence.

References:

- Texas Beyond History Website “Deer Hunting” https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/waco/images/deer_page.html

- R. Blasco, J. Rosell, M. Arilla, A. Margalida, D. Villalba, A. Gopher, R. Barkai. Bone marrow storage and delayed consumption at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel (420 to 200 ka). Science Advances, 2019; 5 (10): eaav9822 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aav9822

- A Neglected Treasure: Salado Creek by Patricia Merrill, © Salado Historical Society 2001.

- From http://www.centraltexasstories.com/places/salado-creek.htm. All Rights Reserved/Charlene Ochsner Carson.