Interview: Veteran Paleontologist Ernie Lundelius

A Look Back on a Long Career in Science and Education from Austin to Australia and Back

Dr. Lundelius holding a short-faced bear skull from the Bonfire Shelter in Val Verde County. Photo by Steve Black c/o Texas Beyond History.

More info about the site HERE.

In 2014 I was looking for help with preserving a nearly complete 700-year old bison skeleton that I had just excavated on family property with David Calame and Bruce Turner from Texas Borderland Archaeology. People kept telling me, “You need to talk to Ernie!” Dr. Ernest Lundelius is a retired UT Professor Emeritus (at that time in his mid-eighties) who still spent a lot of time at the Vertebrate Paleontology Lab on the JJ Pickle Research Campus in north Austin. Someone put us in touch, and he kindly invited me to the lab. I happened to be working at a warehouse down the street at the time, and was able to arrange a few visits during lunch breaks. I lugged my buffalo skull, heavy, crumbling, and filled with soil, into the lab where Ernie and the lab staff demonstrated how to preserve it. I got a glimpse of their incredible collection of fossils, including a massive Triceratops skull, a sprawling Pterodactyl wing on the wall, and a basement filled with skulls and fossils of all kinds. I was grateful for Ernie’s hospitality and expertise.

A few years later, I donated the bison skeleton to the Falls on the Colorado Museum in Marble Falls, where I was surprised and honored to see him show up for the dedication. (Scroll to the bottom of the page to see a timelapse video of the bison excavation made by Bruce Turner.)

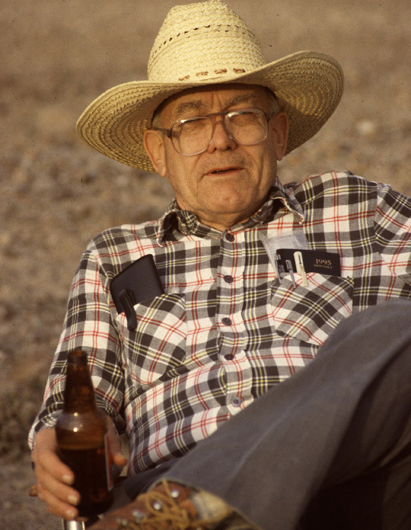

In summer 2025, I caught up with Ernie, now 97, for an interview over lunch at his home in Austin. Here are some excerpts from our chat.

--Ryan Murray, Editor/Publisher

Born in Austin in 1927, Ernie grew up on a farm where he learned about animals and developed an interest in geology and fossils early on. At age 18, when World War II ended, he was drafted and sent to the Philippines and assigned to a unit that was retraining the Philippine army. That was his first teaching experience, and military service helped him pay for college, which led to a long career in Geology and Paleozoology...

R: Do you still have any of those fossils that you collected early on?

E: I think some of them went into the UT collection because they were good specimens and I knew exactly where they came from... I finished my BS in Geology in 1950. Then I went off to the University of Chicago for graduate work in Vertebrate paleontology.

This is another odd thing: when I was an undergrad, Jack Wilson was the vertebrate paleontologist in the department, and he and I got to be pretty close because of my interest. He was very, very helpful. There was a collection from a quarry site a little bit south of Abilene in the Permian that had a fairly large number of skeletal elements from a Dimetrodon. Jack was working on this and said that because of the size range in the bones from that Dimetrodon, there might be more than one species of Dimetrodon in there. Well, I remember at the time, I had taken some ecology courses, and it turned out that the Dimetrodon was probably a carnivore. And we rarely had more than one of those… and you couldn't tell the adults from juveniles easily.

Let me see if I can phrase this. If you have this situation: is there any way you can decide if you have more than one taxonomy, or more than one species? And this didn't occur to me for a while until I was a graduate student, and suddenly it hit me. After I'd had some statistics, what you could do if you had a modern situation, is you could plot with a graph one measurement against another and see if you got two. And I knew how I could test it because right around here, there are two of those big spiny lizards. One lives mostly on the ground and another up in trees. And they are the same genus, it's Gerrhonotus. And I knew I could get it and thought it was a good idea, and I managed to get a very wide age range on both species. I got a bunch of measurements on some of their skeletons and plotted these things for regression and sure enough there are things you can compare where you get some things with species A here and some things with species B there.

Looking at the skeletons, it's very difficult to tell them apart. But that cleared it up. I don't know if anyone has ever really applied it. Those specimens are currently in the Smithsonian.

Lundelius in Australia, 1976 with a goanna lizard. Photo c/o Ernie’s daughter Jennifer Welch.

But then things changed for me rather drastically. The first year I was in Chicago, I met an Australian who was somewhat older than I, and he was like me; he had done a double major of zoology and biology. He told me, ‘Ya know, when you finish your degree you should come out to Australia.’ He was from Western Australia. He said ‘I know some fossil localities out there that you need to look at.’ So I kept in contact with him--in those days by mail. I got a Fulbright, and in the meantime, I had acquired a wife, so we went to Australia and spent a year there. A wonderful year.

R: Was that in the 60s?

E: 1954-55. Boy, that was and still is an empty continent. So we spent a year there, then I came back to Caltech. I came home to Texas to visit and was talking again to Jack and some others, and they said, ‘well look, we lost a guy, and we are looking for somebody in the area that you work in. So tell us what you've been doing.’ So I told them what various things I was doing and they made me an offer of assistant professor, and I took it since there wasn't anything else available! (Chuckles)

R: When they offered you that job, were you able to jump right into it, or did you have to have additional training?

E: No I jumped right in it. With the courses I was asked to teach, one was a freshman geology which was no problem. And let's see… for a while I taught the basic Paleo course too. But I don't remember when I started. But some years later Bill Turnbull at the Chicago Field Museum, who was a good friend, asked me to go back to Australia, but we had another project to do. But then we got money to go back... but by that time Julie and I had two little kids!

R: It sounds like your responsibilities increased tenfold!

E: Oh yeah! (Chuckles)

R: But then somehow you made it back to Austin.

E: After another year in Australia I returned here and have been here ever since. On that second trip to Australia, my daughter Jennifer was about five and my son Rolf was three. We spent a weekend camping by one of the caves and she spent her time reading because she was just learning to read, but Rolph spent his time throwing rocks! We put her in a school there and after about three days she picked up the Australian accent. After we got home we put her back in school here and after about three days, she lost the accent! (Laughs)

R: I was just talking with a friend of mine, David Calame, maybe you know him?

E: I think I remember the name.

R: He dug for many years at the Montell Rockshelter (Uvalde County) after you guys left.

E: Oh yeah.

R: He said he thinks you might be the last one still around who was there at the beginning.

E: That's probably true. I never actually did any work out there, but I did look at all of the bones that came out of there.

R: What do you remember from that site?

E: Not very much! (Laughs) One thing I did do after I came back from Australia was start to look at the deposits from caves. They are usually well preserved.

There are a lot of caves on the Edwards Plateau. There was a lot of material, some of which was earlier collected. There's a cave in Bexar County, the Friesenhahn Cave, that's been known for a long time. And a funny story about this was- I think the first publication on that was from the early 1900s- and then there was E. H. Sellards, arrived in Texas sometime in the 1920s, I think. And he was interested in early man in North America. And he went and talked to old man Friesenhahn, who owned the ranch that it was on, about going back in there--and the old man wouldn't let him on. And the old man's explanation was that those bones been there so long that he didn't think it was right to disturb them. And that was that until the old guy died, then his sons were running the ranch. And this was after the Second World War, and they went back, and Glenn Evans… well, Glenn is one of the more knowledgeable people around here, they went down there, and he came back saying there were a bunch of concrete castings in there. And then we went, “Ohhhh. Now we know why the old man didn't want him in there.” He had a still in that cave and it was during prohibition! Glenn told me nah, it was just a water trough that had gone bad (Laughs). I’ll take Glenn's word for it.

R: My friend that I was talking about, David, he wanted me to mention to you that they found a Paleo point with charcoal samples there long after you guys had left that pushed the occupation of the Montell cave to 11,000 years. The point type is called Milnesand, which is similar to a Plainview point type.

E: Yeah. I vaguely remember that. I didn't want to intrude on the other people who were working on that though.

R: David was telling me another funny story. Some years ago they found an old test hole at Montell, and there were some goat bones in there. He brought them to you at the lab, not knowing what they were, thinking they were prehistoric. You looked at them and determined that they were modern goat bones. Somebody had eaten one of Vic Rogers' goats and tossed the bones in the test hole there.

E: (Laughs) I don't remember that but I probably would've done that!

R: What did they find there that they called you in to look at?

E: Well, all of those shelters, if you go back five or six thousand years, you begin to pick up small animals that don't live there today because the planet has changed. And that was a thing that got me interested because I found this to be true in caves in Australia. It's true in nearly every one of those caves. You might find a couple of species of shrews, couple of species of rodents that don't live here today, but they moved to the north and the east where the climates are cooler and summers and winters are not quite so extreme.

The other thing you find is that if you go back beyond about ten or twelve thousand years, you begin to get the bones of extinct animals, like fragments of mammoths and some of the big cats. Friesenhahn, for example, had the remains of three big cats. One is a sabertooth, the other is an odd cat that had canines about like this (gestures with fingers to show size) like knives, and it's got relatively long legs for a cat. And if you look at the claws on most big cats, they look like great big hooks. These are not; so that animal was operating in a very different way than other big cats. Then there's the remains of a standard lion, a big guy that stands about that tall (gestures with hands). You don't wanna mess with them!

But that raises an interesting question, which has not been answered... there’s a lady at Vanderbilt, [Larissa DeSantis], she’s done a lot of work on the isotopic remains of bones, and you get a lot of good information from that. She looked at the carbon isotopes in this weird cat from Friesenhahn and the concentration of the C-13, and that suggested that it was preying on animals that were eating grass, because grass has a different synthetic pathway than bushes and so-forth, with so-called C-4. Now, we suspected that was the case, because there’s a lot of young mammoth bones at Friesenhahn. It was one more confirmation that maybe that’s what they were preying on. If we could do that, we would get more information than we ever dreamed we’d get otherwise.

R: Do you think there are any pristine caves left in Texas that haven't been found?

E: Probably. But there's a lot to be done on the caves we know. We could do more on Freisenhahn. There's another cave in Kerr county which is Hall's Cave. The first real expedition of it was done by a student of mine. It's on the Hall Ranch, and this guy that owned it at the time was really helpful and cooperative. So we were able to do a couple of things to help him out off and on. Rick Toomey dug that cave, and that was gonna be his dissertation. He and I talked about it, and we were up there, and he said "I propose to dig this down 5 cm at a time and sift everything." Well, that's a hell of a lot of work! (Laughs)

R: Painstaking!

E: But he did it. Down to two-plus meters and got faunals all the way down, and there was a minor change in the ratio of the small animals... at I think about five or six thousand years in the case of a climatic change at that time, and then it comes back. And this matches with data from other sources of a climatic change at the same time. So it was really beautiful stuff. Now we have a large number of radiocarbon dates all the way down- I don't remember all the numbers now though. But Rick wrote this great big two-volume dissertation, but it was never published. I haven't heard from him in a while but he has a job in Kentucky in some academic department. I think Rick set the standards that other people have sort of followed. And it would be great if somebody could go back to Hall's cave and take a good, hard look and see if they can get anything with DNA out of it.

Ernie at age 82 back in Australia in 2009, lowering into Leaena Breath Cave. Photo c/o Welch.

R: I did see you on TV recently, I guess you are a movie star now. Did you know you were in the new movie about the Gault site?

E: I haven't seen it, but I saw Mike Collins here about two weeks ago.

R: A lady named Olive Talley made a movie about Mike and the Gault site that was recently shown on PBS.

NOTE: The documentary is called "The Stones Are Speaking" and info about the film and how to watch it can be found at thestonesarespeaking.com

E: Is that right?!

R: Yeah, I was watching it with my wife and I said, “Hey rewind that, I think that was Ernie!”

E: Is that right! (Chuckles)

R: What was your involvement with the Gault site and Dr. Collins?

E: Mike was one of my students, because at the time it was my early years of teaching, sometime in the first two or three years. He was a student at Anthropology. He came over and took some geology courses and he took several that I was teaching, and he and I became very good friends. Mike is one smart guy, let me tell ya. And that friendship has lasted. He was here the other day. I visited the Gault site a number of times when they were working. They got the lower jaws of a mammoth out of that site, you know?

R: Yes, I got to meet Howard and Doris Lindsey, the couple who live out there and found it. They were very nice. I had the honor of being invited out there recently and Mike was there too. He was back in his element; he remembered everything. We walked around and he was pointing things out and he recalled everyone's names and what they did in each spot. The Lindseys live right next to the site, and they invited us into their home. And I guess they hadn't seen Mike in a year or two. They brought us in and Mrs. Lindsey made us some fried pies so I got to tag along and witness their reunion. It was really nice.

E: That's good.

R: And I saw that (mammoth) mandible at TARL (Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory) a few days ago. Did you do any work with it?

E: I think I helped them collect it, but I didn't do anything with the faunal material there. But there's always a bunch of students that are looking for projects, and from my point of view they were good for a student: Tell us about this… Identify all this stuff… What does it mean? But anyway, that's an important site. A lot of the bones that they pulled out of there were so fragmented that you couldn't tell what they were. It occurred to me that we need a cheap way to extract DNA so we can tell what species they were from. But as far as I know there's not a cheap way to do that.

R: And the DNA deteriorates over time.

E: Yes, but it also shows up in odd places sometimes.

R: The site is covered up now, all of the holes are filled in and cattle are grazing on it now.

E: Is that right?

R: But it's preserved through Mike's purchase of the land.

E: Yep. I know he owns it.

R: My understanding is that he bought the land, and the Gault School of Archaeological Research, which he started, are the stewards and caretakers, and Mike donated the land to the Archaeological Conservancy who has ownership.

E: OK that's right. I'll have to watch that movie.

Juvenile Columbian mammoth mandible found at the Gault Site near the border of Bell and Williamson Counties

E: I liked teaching. I learned a lot. Sometimes I think I learned as much from my students as they learned from me. It's interesting because I usually had answers for them, but I had never had the questions asked in that way, so I had to think about it. You learn something that way.

R: Can you recall your proudest moment as a teacher?

E: I can't remember exactly, but some of my graduate students have done so well, and I really feel good about that. Oh, I'll tell you one thing. One day, I was walking across campus and a young lady walked up and she said, do you remember me? I said 'sorry, I don't,' (chuckles). She said, "I took your freshman physical geology course last year, and this summer we went to Europe and took the train from Italy up through the Alps to Switzerland." And I've been on that train, but she said, "I saw in the cross section of the mountains overturned boulders and I knew what it was!" And I thought, by golly, for once... (Chuckles) But it's true, you can see a fair amount of stuff if you look out the windows when you are going through the Alps.

R: So your career took you all over the world. What made you come back to Texas?

E: The job.

R: Do you think you would be somewhere else if you wouldn't have gotten that job?

E: There was talk at the time of an opening at the Smithsonian. But it didn't pan out, or something happened. Now that would have been a hard choice. But anyway, I'm not unhappy at all, I’ve had a good time here.

R: Well, thinking about just the places in Texas where you have worked, what are some of the more remarkable things that stand out in your mind? Like locations or things that you found?

E: Well, I guess one of the most interesting and complicated things is that cave up there next to Georgetown, Inner Space.

There were two or three of us who were the first few people to go in that cave and we got in through a big bore hole. And they had discovered this thing because they were doing the drilling foundation for the interstate (35) and they got down about 30 feet or so and the whole thing just kinda (makes a sound and hand motion of a collapse of the ground) into a cave. Well, two or three drill holes, and they finally brought in this thing that drills a great big hole like that (makes hand motion) and pulls a big core out. And you go down on a rope… But finally, they opened it up, and you walk in.

That's a complicated cave because it sits right on the Balcones Fault. Which of course, there's more than one fracture. Which means that there are many, or originally at least, four openings... and we had radiocarbon dates on three, which had some faunas, and two of the dates are close, around 12,000 and 14,000 and the third one is about 23,000 years old. And the faunas, which are not very large, they are the same in the first two, but there's some things in the older one. And one of this is--if the absence of those animals is just pure chance--I'm not quite sure. But the older one has things like the Glyptodon and a couple of sloth remains. Anyway, it's a complicated cave and there's a fellow named John Moretti who's since finished a PhD on that cave, looking at trying to sort out all of the complexities, so you might look him up. He's here in Austin and he's a good guy. He'd be happy to tell you about it.

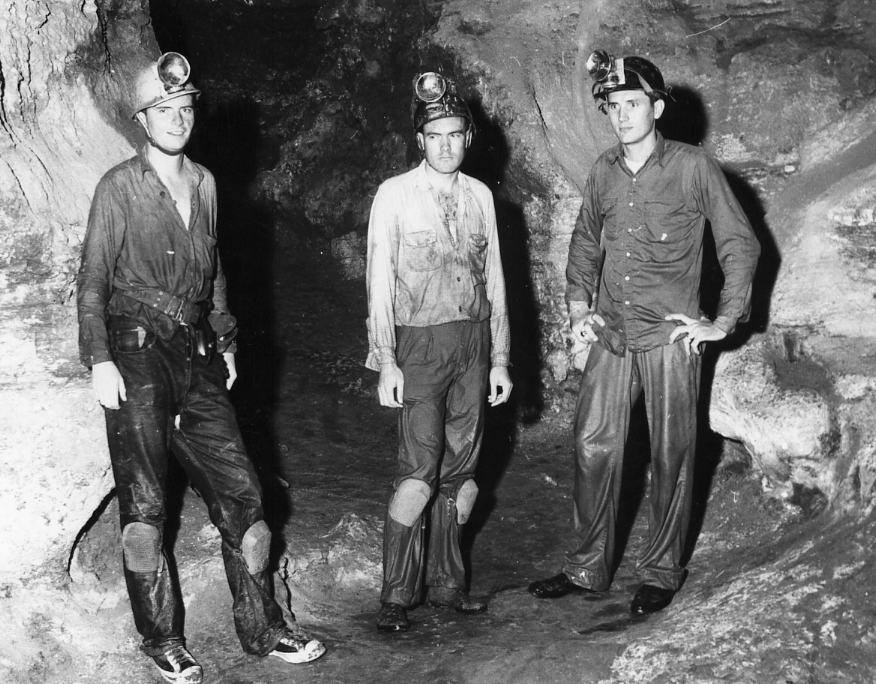

Holmes Semken, Jr., Ernie Lundelius, and K. Baker exploring Longhorn Cavern in Burnet County, circa 1957. Photo c/o University of Texas Paleontology Collections.

R: Can you think of your greatest discovery?

E: I'm trying to think… maybe in a sense, although it never made it any news, in Western Australia, there is a limestone-based plateau very much like the Edwards. It's a much bigger area, the so-called Nullabor Plain, and it's a desert, or pretty close to one. This was the first year I was there, and the road from Adelaide, the city in South Australia to Perth--it's a long way, more than 1000 miles--and it goes across what's called the Eyre highway, which in those days was unpaved. (Laughs) I've driven it! But there are a lot of limestone caves along that road. And one of them is Madura Cave.

R: Didn't you write a book about that?

E: I wrote a paper about it. Matter of fact, when Bill Turnbull and I went back, I can't remember what year, we dug that cave more carefully. And we've written a number of papers on the fauna: marsupials and so forth. Well, back about 20,000 years, there were koalas living out there. Now, koalas require a forest. There's no forest within 1000 miles today. So there was a big climate change there. That's the big one. Maybe it's in the big five... but that's been published in the publications of the Field Museum.

And there's one thing, the rodents and the bats, we got those out of there too. But Bill and I wrote the paper; we didn't quite get it cleaned up, but then Bill died, and I sort of let it go. And recently, I met a man who had a helper who said he would help update it. Somebody needs to go back because there's more stuff in that cave. Somebody needs to go back and emulate Toomey and go 5 cm at a time.

R: How long does it take going 5 cm at a time to get to 2 meters?

E: Screening a square grid carefully, you're looking at two or three hours' work, maybe more sometimes. It's painstaking work.

R: Did you ever experience any dangerous conditions while excavating? Any close calls?

E: Never had a close call, but let's see, there was one cave I went in, I can't remember where it is, but I never went back because there were too many great big boulders. I decided it wasn't worth going in again. I'd have to go back and look at my notes, but I don't think I've ever been in a cave here in Texas that I regarded as dangerous. But you can always slip and fall!

R: Or choke on the dust inside some of those rock shelters!

E: Yep!

R: Well, it's 1:30 and I know you need to get going soon. I really appreciate you having lunch and chatting with me. Ya know, the last time I was in this neighborhood, my wife was giving birth to our daughter at the hospital down the road. And that's been five years now.

E. That's great! I remember when my daughter was born here in Austin and the nurses brought her out. I couldn't believe the noises that were coming out of that tiny little baby. And ya know, my first thought was, “Holy $#!+ Now I have to be responsible!” (Both laughing) But she turned out very good.

Photo c/o Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas.

Below: See the video of the bison excavation mentioned at the beggining of the article made by Bruce Turner...